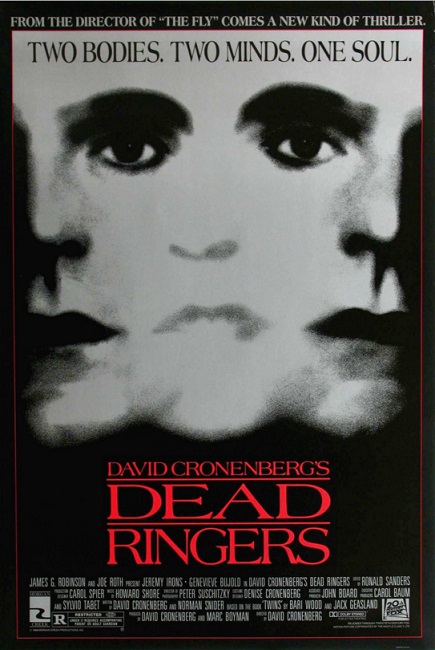

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Dead Ringers (1988) Film Review

Dead Ringers

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

In early September 1975, the decaying bodies of twin brothers Stewart and Cyril Marcus were found in their apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan by a repairman following up on complaints about the smell of the place. Both had worked as gynaecologists at New York Hospital and their deaths were eventually attributed to a misguided attempt to go cold turkey after prolonged use of drugs to which this career had given them access. The story caught the public imagination and led to the publication of a book, Twins, by Bari Wood and Jack Geasland. David Cronenberg’s film (itself now the inspiration for a mini-series starring Rachel Weisz) draws partly on the book and partly on the brothers’ real story, with moments from their lives – such as a shocking incident in an operating room – woven into his fiction.

There is a public fascination with twins which, where women are concerned, often involves sexual objectification. In a nod to that, this film briefly features twin call girls, but where Cronenberg pushed boundaries was in exploring the sexuality – and especially the sexual vulnerability – of male characters. The film opens when Elliot and Beverly are still children, comparing notes on the evolution of sex and sexual dimorphism. “They’re so different from us,” says one, of girls. “And all because we don’t live underwater.” Throughout, there is a sense that the twins feel sexually alienated, all their acquired medical knowledge bringing them no closer to recognising the humanity of women, or even of other men. Where some people lack empathy entirely, they can feel it for one another, but their inability to form meaningful connections beyond that bond makes them desperately co-dependent.

“Do you share a bed?” asks actress Claire (Geneviève Bujold), a client of Elliot’s who crosses one ethical boundary by embarking on an affair with his brother and then gradually figures out that she’s been sleeping with both of them. Cronenberg reportedly spent some time talking to Peter Greenaway about A Zed & Two Noughts before embarking on the film and there are similarities between Bujold’s role here and Andréa Ferréol’s in that film, with broken symmetry throwing everything off balance. The ostensibly more sensitive Beverly’s infatuation with Claire draws him away from Elliot, whom she perceives as having exploited them both, but as she is unable to provide him with an equivalent full time support system, he becomes dangerously unstable, increasingly reliant on drugs to fill the gap. Elliot, meanwhile, proves ready to do anything – no matter how self-destructive – to maintain that filial closeness, in the process exposing his own vulnerabilities and the flimsiness of his smugly self-confident façade.

Jeremy Irons’ multi-award winning dual performances as the twins imbue the whole with a humanity not always present in Cronenberg’s earlier work, inviting viewers to feel for these troubled men despite recognising the monstrousness of their behaviour and attitudes to women. Key to this is his resistance to the idea of having a ‘good twin’ and a ‘bad twin’ – both are complex, multifaceted individuals. Pay attention and it is possible to distinguish them by small behavioural details even when it isn’t immediately obvious which one we’re with, even as Elliot begins to lose his own identity in his efforts to reconnect with Beverly. One is reminded of Hitchcock’s take on the Leopold and Loeb murder case in Rope, in that the real potential for danger lies as much in weakness as in strength.

Though the spaces which the twins inhabit initially have the sterile quality which one would expect in a medical setting or the simple elegance which signals their wealth, Cronenberg positions his camera in ways which suggest gradually escalating disorder. The angled walls and windows in Elliot’s office recall German expressionism, and this is a form which the director references with increasing frequency later in the film. It suggests both psychological imbalance and an obsessive sense of destiny which makes it impossible for the brothers to escape the fate which they have created for themselves.

There is, naturally, a good deal here about the trepidation with which many women approach gynaecology, and the power imbalance which results from the profession’s domination by men. This is most overtly manifest in Beverly’s efforts to get disturbing new surgical tools made for him by an artist, “for operating on mutant women” – symbolic of his externalisation of his inner conflicts – but it also emerges more subtly in the expectations expressed by various women in conversation, illustrating that a visit to such a doctor is one in which pain and humiliation are treated as par for the course. The grand Gothic of the twins’ tragedy plays out against a background which is already horrific, and the more so for its normality.

There is an additional layer of weirdness in watching the film today, now that some of the gynaecological techniques which it references have been superceded, but plenty of patients will still relate strongly to the picture of the specialism which it creates. It allows for a very particular form of objectification, which Claire counters directly in a manner clearly unsettling to Beverly, precipitating his efforts to divide women into two classes as many misogynist men do after finding one they like. By separating misogyny from the directly sexual, and magnifying his male subjects through their twindom, Cronenberg is able to explore the defensive mechanisms behind it, the perceived threat to the masculine ego and terror associated with emerging from carefully reinforced delusions into the real world, which parallels the danger which the brothers face in quitting drugs. Unusually for him, there is very little distortion of the viewers’ perspective, as he trusts Irons to carry these aspects of the story through acting alone.

What emerges is a sensitive yet intellectually robust work which, due to its genre positioning, has never really received the attention it deserves. It is in many ways Cronenberg’s most interesting film, and certainly his boldest, required viewing for anyone with an interest in his creations. As compelling as it is uncomfortable, it is long overdue a revival.

Reviewed on: 11 May 2023